It’s a question that has likely crossed your mind after seeing a sudden summer swarm: we always see ants crawling, but do they ever fly? The short answer is yes, but the full story is a fascinating look into the highly organized and complex world of an ant colony.

For the vast majority of ants, life is spent entirely on the ground. But for a select few, at a very specific time, the sky calls. This guide explains who gets to fly, why it happens, and what this incredible event means for the survival of the species.

The Simple Answer: A Qualified "Yes"

Yes, some ants can fly. However, this ability is temporary and reserved exclusively for the reproductive members of a mature colony, known as "alates." The wingless worker ants you see every day will never develop wings or be able to fly.

Who Flies: New, fertile queens and males (alates).

Why They Fly: To leave their home nest and mate with ants from other colonies. This event is called the "nuptial flight."

The Catch: The flight lasts for just a few hours. Afterward, the males die, and the queens land, break off their own wings, and never fly again.

[Here: An engaging animated video explaining the different castes within an ant colony and their specific roles—worker, queen, and alate.]

Not All Ants Are Created Equal: The Winged Caste

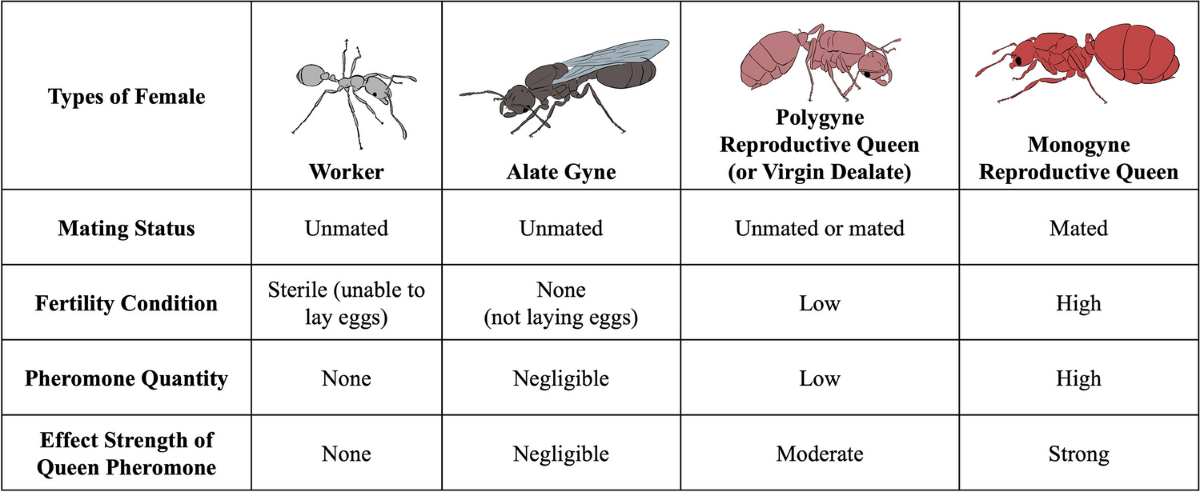

An ant colony is a superorganism with a strict caste system. Each ant is born into a role, and this role determines if it will ever have wings.

Workers: These are all sterile female ants. Their job is to find food, defend the nest, and care for the queen and her young. They are built for life on the ground and are wingless.

Alates (The Flyers): When a colony is several years old and thriving, the queen will begin to lay eggs that develop into a special reproductive caste. These are the alates. According to scientific resources like the Natural History Museum, the development into an alate versus a worker is often determined by environmental factors and the nutrition the larva receives. The alates are born with wings and are destined for one thing only: the nuptial flight.

Caption: Wings are a feature reserved for the reproductive caste (alates), not the common worker ant.

The Nuptial Flight: The Only Day an Ant Takes to the Sky

The sole reason any ant has wings is to participate in the nuptial flight. This is a mass, synchronized mating event that is often referred to as "Flying Ant Day."

Driven by precise environmental cues—typically a hot, humid day with low wind after a rainstorm—thousands of alates from countless colonies in a region will emerge and take flight at the same time. This synchronization is crucial for two reasons:

To Ensure Genetic Diversity: By flying and mixing high in the air, males and queens from different nests can mate, preventing inbreeding and keeping the species genetically strong.

To Overwhelm Predators: The sheer number of flying ants overwhelms predators like birds and dragonflies. This "safety in numbers" strategy ensures that, while many are eaten, a vast number will survive to reproduce successfully.

After this brief aerial event, the life of a flying ant changes dramatically. The male alates die shortly after mating. The newly fertilized queens land, find a suitable location, and then use their legs to physically break off their wings, as their life of flight is over forever. They then begin the solitary work of digging a nest to become the wingless mother of a new colony.

A Quick Word of Caution: The Termite Impostor

Because the sight of any winged insect can cause concern, it's always important to distinguish harmless flying ants from destructive termites.

Quick Check: Remember that ants have pinched waists and bent antennae. Termites, their look-alikes, have broad waists and straight antennae.

In conclusion, the answer to "do ants fly?" reveals a story of specialization and survival. Flight is not a common skill but a temporary, vital gift bestowed upon a chosen few. It’s the single, critical act that allows the legacy of the colony to spread and begin anew. The next time you see a swarm, you’ll know you are not just seeing insects, but the flight of future kings and queens.